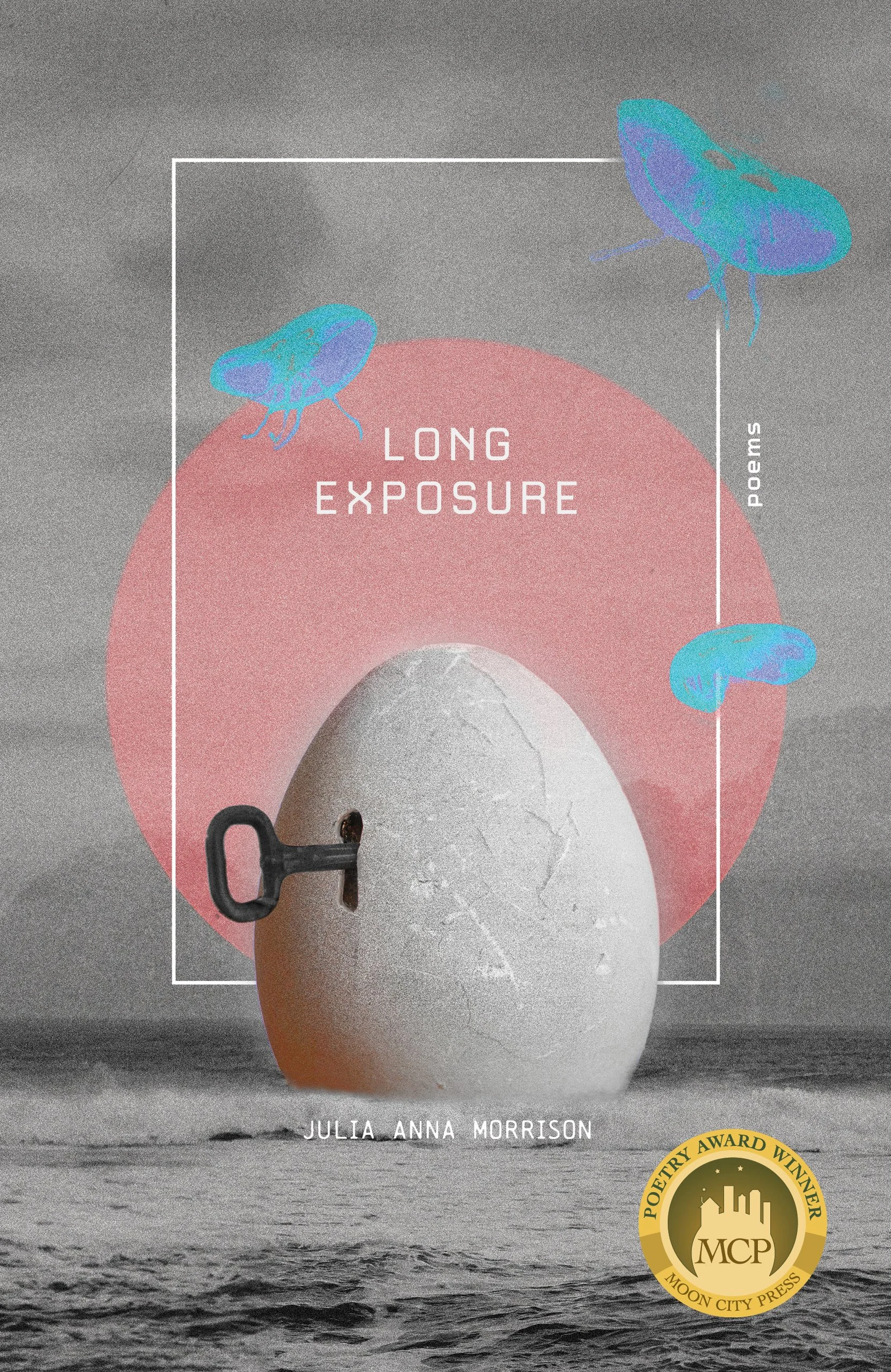

Long Exposure follows a woman in the years after her son’s birth as she struggles with postpartum depression and a painful separation from her child’s father. Forced to reckon with her own childhood experiences, including the death of her brother to an accidental overdose, the speaker examines, as if through a camera lens, memories videotaped together. The book explores familial grief, addiction, and mental illness through language both surreal and plain, domesticated and haunted. These poems ask what it means to be an artist and a mother, outside of female friendships and romantic relationships. The poems, experienced as part fever dream, part damaged video footage, exist in a darkly overgrown and hypnotic landscape. Ultimately, the book is a portrait of a speaker locating many selves from long ago, resurrecting what images she can from the recovered video footage of her personal archive.

excerpt from book review by Loisa Fenichell in Pleiades